Research Engine

A University where high-tech thinking meets hands-on solutions

It’s right here, in this field of food, where high-tech thinking meets hands-on solutions.

Certainly farmers are already using technology in various ways, but as a traditionally blue-collar occupation, farming is perhaps one of the final industries to undergo a full technological overhaul. And if managing water usage, labor costs, production and profit margins are the challenges, student and faculty researchers at Fresno State want to be a part of the solution.

Unmanned aircraft systems research started at Fresno State 10 years ago and has accelerated with a five-year grant from the University of California Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources. The grant helped researchers within Fresno State’s Lyles College of Engineering pivot their unmanned systems development from military applications to farming solutions specific to the Central Valley. Their work, though still in prototype testing stages, has piqued the interest of Rollin, president of the Executive Committee for the Fresno County Farm Bureau, and other key players in Valley agriculture. And it has led to additional collaboration with Fresno State’s Jordan College of Agricultural Sciences and Technology and AeroVironment, Inc., a global leader in unmanned aircraft systems.

Testing, Testing

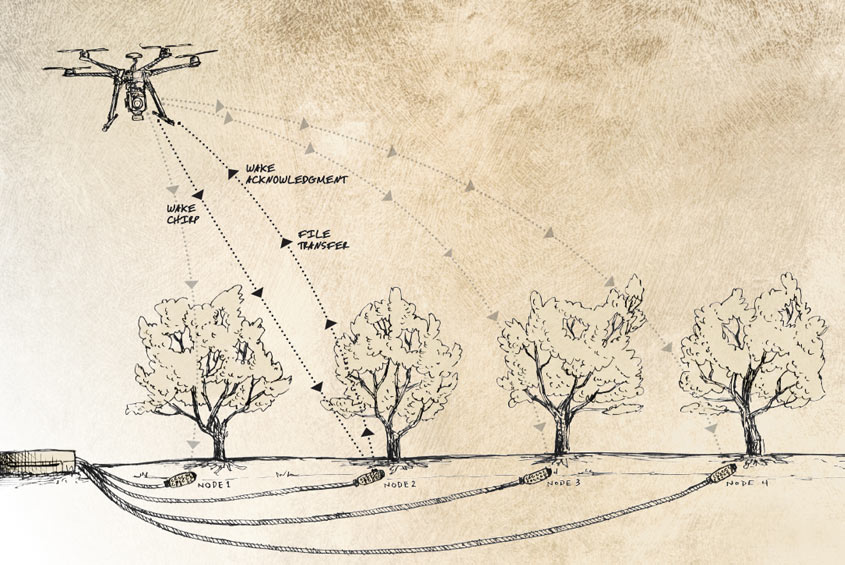

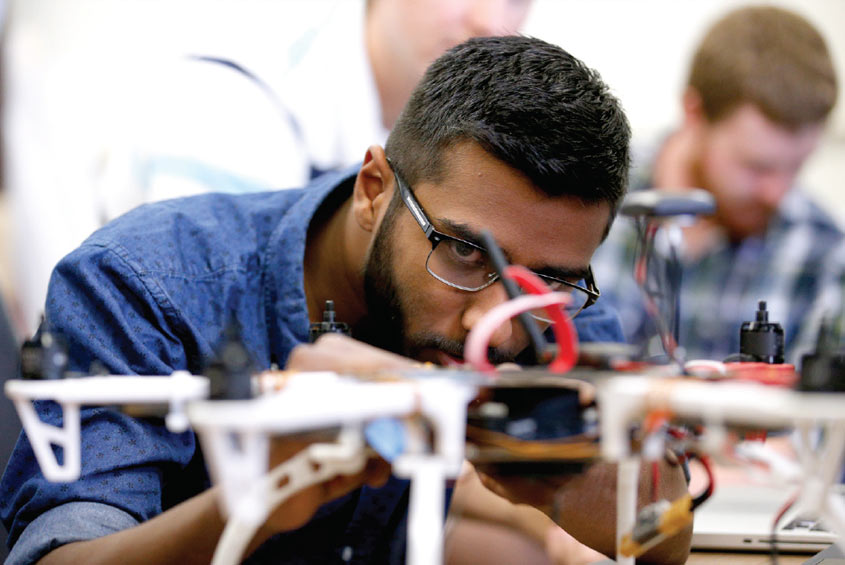

In the spring, Fresno State engineering professor Dr. Gregory Kriehn led a group of students in a field test on Rollin’s Riverdale almond orchard. The students strategically placed throughout the almond orchard the embedded ground sensor systems they developed in the lab to measure temperature, humidity and soil moisture. With Kriehn at the flight controls, the group launched a series of unmanned aircraft systems — both fixed wing and rotary wing — that flew over the orchard taking video and still photos while signaling the ground nodes to wirelessly transmit data to the motherboard on the aircraft above (see diagram). Throughout the process, students watched in real time as data was collected and displayed on monitors they positioned on a tabletop near the field.

“The end goal for this particular grant is taking a look at stress in almond and pistachio orchards,” Kriehn says. “With the drought that’s been hitting California hard, growers are trying to determine how much stress a tree can be under from a water perspective before it starts to affect the tree’s nutting capabilities. There’s a direct correlation between how much water the tree pulls to how much nutting occurs.”

Historically, the only other way to determine water stress and the potential production of almond and pistachio trees was to place a leaf in a pressure chamber to measure the amount of pressure it takes to cause water to appear at the stem. The more pressure it takes, the higher the degree of water stress on the tree.

For almonds, the highest grossing crop in Fresno County at $1.2 billion in production in 2015, measuring water stress helps ensure proper irrigation in growing season and avoid over-irrigation during hull split, which can lead to disease.

Discovery

Kriehn and his students, engineers by trade, hope they’ve found a better way to measure crop stress and predict yield. They have done their homework on agricultural quality and efficiency to fully understand industry needs.

This research project was a natural fit for Freddy Lopez, a student pursuing a master’s degree in computer engineering.

Lopez lived in Selma on 20 acres of grapes until age 10 before moving to Clovis, where his family works as farm labor contractors and produce brokers. Lopez himself started a well water monitoring business named WaterMap Tech in 2016, taking advantage of a Fresno State program called Innoventures that was started by Lyles College Dean Dr. Ram Nunna to help students receive funding and mentoring for innovative ideas.

Lopez understands he and his fellow students and faculty will need to demonstrate a return on investment for their work to become viable. “The farmers are smart, they’ve been in business a long time and know what their margins are,” Lopez says. “We’re talking about people who plant trees and wait up to 10 years to get their money back. They’ll use technology, but you have to convince them first.”

While increasing water efficiency and yield is the main draw for the project, the technology also has the potential to identify other nutrient deficiencies or diseased trees. Aerial imaging over a two-week period has been proven to pinpoint specific trees that have pest infestation — a useful tool for farmers managing dozens or even hundreds of acres of trees that would otherwise be inspected row by row on foot or by tractor.

“If you can get a few bucks an acre, and you’re farming enough acres, all of the sudden it’s a big chunk of money,” says Rollin, who has been a partner and owner of his family’s dairy and farming operation for 22 years and grew up working the land with his father. “If we’re going to generate a profit so we can stay in business, we’ve got to figure out those little things that we can do to be more efficient. If we can get an extra 100 pounds per acre this year because we did something with the technology of the drone, maybe it’s paid for in one year.”

Preparing for Takeoff

Right now, the use of unmanned aircraft systems such as those Kriehn and his students are developing is rare in agriculture and limited mostly to very large farming corporations. It’s the “early adopter phase,” says Ryan Jacobsen, the CEO and executive director for the Fresno County Farm Bureau.

“We’re in the infancy side of things,” says Jacobsen, a fourth-generation farmer who earned his M.B.A. from Fresno State in 2004 and formerly served as student body president. “In a short number of years, most farmers and ranchers will be taking advantage of some aspect of the technology as it becomes more affordable and usable. These tools don’t become optional, they become part of your operation.”

Jacobsen is eager to see how the collective wisdom of faculty and students can merge with the needs of farmers and ranchers to develop technology-based solutions for agriculture. He echoes Rollin’s sentiment that water usage and labor costs present critical challenges for the industry’s future.

While a year of heavy rainfall throughout the state led to California Gov. Jerry Brown declaring an end to the drought in most counties in April, several Valley counties — Fresno, Kings, Tulare and Tuolumne — remain on alert after one of the driest five-year periods in recorded history.

Without enough water allocated to farmers, Rollin cautions, there would be empty shelves in the store pretty quickly.

“They say whiskey is for drinking and water is for fighting, and that’s the truth,” Rollin says. “We’ve got to have water to do everything from have a nice, green lawn to have enough water for people to drink and to grow food.”

Solving issues so large and complex will surely require government involvement. And the economic success of the Central Valley may depend on it. At Fresno State, expanding water-related majors, creating stronger industry partnerships and building cross-college opportunities for applied research such as unmanned systems are part of the mission outlined by the President’s Commission for the Future of Agriculture set in motion by University President Joseph I. Castro in 2013 to position Fresno State as a front-runner in ag leadership and innovation.

For engineering and agriculture students and faculty at Fresno State, that means ramping up research and collaboration to an all-time high inside the labs of the Jordan Agricultural Research Center in hopes of sparking an idea that resonates worldwide and helps farmers conserve water and control costs like never before.

They’ll develop these ideas, build something in the lab, take it to the farm to test it, bring it back for refinement and continue that cycle.

“We’re right here on the back doorstep of the most productive agricultural region of the world,” Rollin says, “and to have Fresno State grasp on and partner with us, that’s a tremendous benefit to both us as farmers and to students, giving them something exciting and new to look at, something cutting edge, something that can change the world.”

— Eddie Hughes is senior editor for Fresno State Magazine.